Unravelling Hinduism: Basic Religious Principles

I read “Sanatana Dharma: An Elementary Textbook of Hindu Religion and Ethics” so you don’t have to.

I am sure that some of us have both the time and intellect to delve into and understand the Hindu scriptures. However for most of us (myself included) this is probably more than we can handle. Therefore I found the aforementioned book (Sanatana Dharma) and read it to gain a better understanding of my religion and the rituals and practices which define life in Nepal for a lot of people. Even this textbook version of Hinduism was a challenge to understand and process, though I have tried my best to root out the key takeaways and major points of importance and plan to share them with you all.

Over the next few weeks, I will attempt to break the vast and confusing Hindu teachings down into smaller more accessible “bite sized” chunks. In this first part, we will take a look at a simplified breakdown of the most basic principles of the Hindu religion. We look at topics such as God, creation, the self, re-birth, karma, sacrifice and the worlds.

What I learned from the information that follows is that Hinduism is a very scientific religion. Hinduism not only talks about God creating the universe but also teaches us how atoms, matter and evolution are all the will of God. The modern scientific idea of the evolution of single celled organisms into Homo Sapiens fits almost perfectly with Hindu teachings that are thousands of years old. Furthermore, even from just these basic Hindu principles we can see how important it is that we realise how interconnected and interdependent every living thing is. I found this teaching very poignant in relation to the environment and the way we treat our planet. The Hindu notion of interdependence is one that we should perhaps revisit as a global society as it will remind us that we cannot continue to destroy our planet and hope to survive the consequences.

What is Hinduism?

Hinduism is known as the Sanatana Dharma, which means the eternal religion and ancient law. Initially the religion was referred to as the Aryan religion after the race of people who settled in what is now the northern part of modern day India in an area called Aryavarta. The word Aryan means “noble” and refers to a race of people greater than all the others who had settled in that particular region. Later the religion was renamed as Hinduism and claims to be the oldest living religion in the world today.

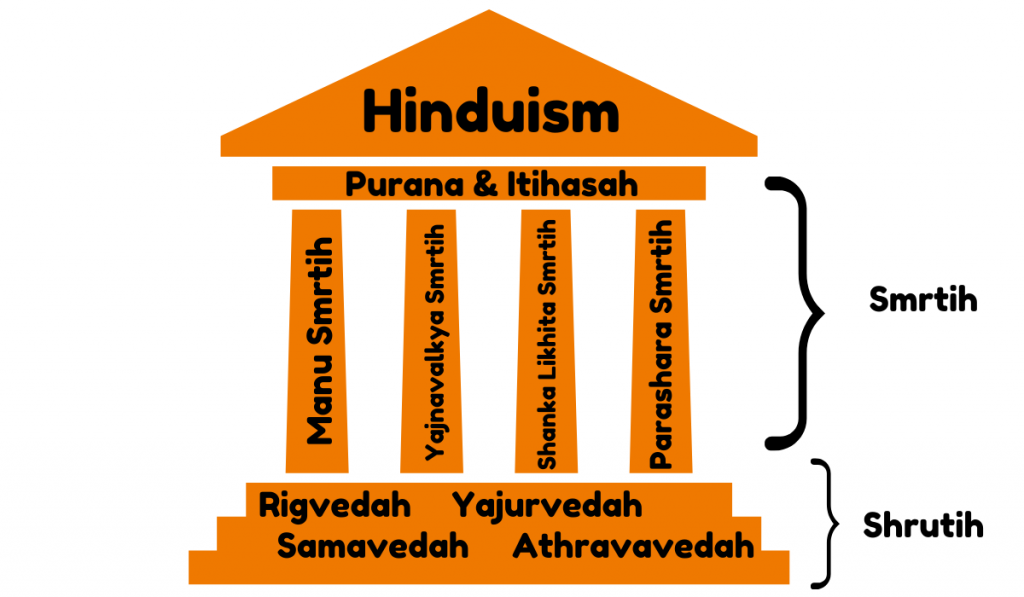

The foundational base of Hinduism is known that “Shrutih” which means “that which has been heard” and upon the foundation of Shrutih are the pillars of “Smrtih” which means “that which has been remembered.”

Shrutih tells us undeniable truths through the four Vedas: the Rigvedah, Samavedah, Yajurveda and Athravavedah. Each of the Vedas is subdivided into three parts: 1) Mantrah, which consist of hymns that portray the relations between Devas (deities) and humans. These hymns should be said repeatedly during ceremonies to achieve our desired end. 2) Brahmanam, which are sets of instructions regarding rituals and stories which tell us how the Matrahs should be used. 3) Upanishat which are philosophical teachings. It is also worth noting that there was a fourth part to each of the Vedas known as the 4) Upavedah or Tantram which consisted of ancient scientific knowledge known as Tantra but that this knowledge has been lost throughout time and little of it remains today.

Smrtih is also known as Dharma Shastra and is secondary to Shrutih in Hindu teachings. Smrtih is thought to have been written by sages and learned men and outlines the laws which govern Hindu society. These laws are divided into the following subsections: 1) Manu Smrtih which is also known as Manava Dharma Shastram and is a compendium of Aryan laws. 2) Yajnavalkya Smrtih which outlines rules similar to the Manu Smrtih. 3) Shankha Likhita Smrtih and 4) Parashara Smrtih.

The Puranas are also an important part of Sanatana Dharma as they are a collection of stories and allegories which were thought to have been composed for those who could not study the Vedas. Primarily this would have been aimed at those who were of a lower class, as only learned men would have access to the Vedas. Additionally the Itihasah are also important. Itihasa means history and in Hinduism this is a reference to the Ramayanam and Mahabharatam.

Thus the fundamental pillars which form the edifice of Hinduism are: Shrutih, Smrtih, Puranas, and Itihasah.

Science in Hinduism was divided into the Six Angas, meaning the six limbs. In modern day we would refer to these areas of knowledge as secular knowledge. The Six Angas are: 1. Grammar 2. Philology 3. Astrology 4. Poetry 5. 64 other sciences, arts and their methods.

Philosophy is similarly divided into six parts known as the Six Darshanas. Darshanas are ways of viewing matters, and the six Darshanas can be visualised as six different roads which all reach the same destination. All of the Darshanas ultimately aim to put an end to human pain and allow the human self to reunite with the supreme Self through the development of wisdom. To the modern mind, these six systems of philosophy present an interesting melding of secular and religious thinking, though in the past there was little to no distinction between secular and religious life.

The six Darshanas are as follows: 1) Nyaya and 2) Vaisheskia, both of which explain how man gains wisdom and how god created the world out of atoms and molecules. 3) Sankhya which explains nature and matter and how these two relate to one another. 4) Yoga which explains the senses and organs and how these can be developed to seek god and our innermost spirit, which are thought to be one and the same. 5) Mimansa, which explains Karma and 6) Vedanta which explains the true nature of God (also known as the Atma) and how we can live free from Karma, practice Yoga and understand the Maya Shakti of God to gain Moksha.

“There is one Infinite Eternal, Changeless Existence”

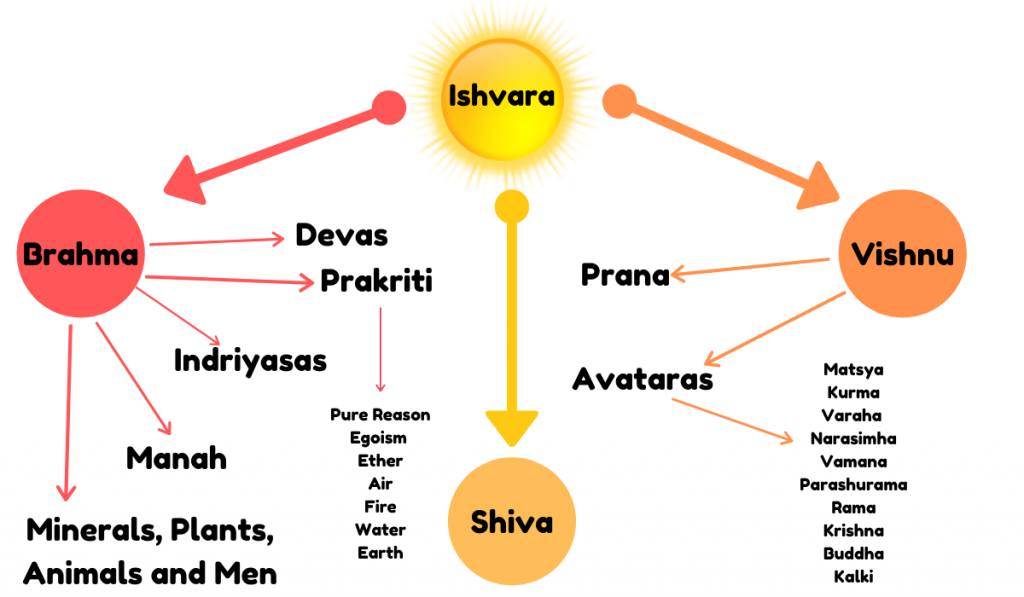

Hinduism presents God as The One Existence, and presents this as the source of everything in the Universe. This Existence is known as Brahman and he is the one who sustains the three worlds. Brahman is also known as Ishvara or Prushottama.

There are two states of Brahman: the Nirguna Brahman who is the one without attributes and the Saguna Brahman who is the version of Brahman revealed to us.

Through Brahman, Mulaprakriti was revealed to us. Mulaprakitiri or Prakriti is the matter which makes up everything, and within everything made up of Prakriti there is a spirit; namely a piece of Ishavara. Maya is the divine power which Ishvara uses to mould matter into different forms.

This means that in Hindu thinking there is god in everything in the universe. This spirit is a piece of Atma (the one who gives life to all) and in all things made of matter the spirit is referred to as Jivatma or Jiva. Human beings are able to perceive matter of all forms, but are not able to perceive the spirit because the spirit and matter are opposites: matter is always changing but the spirit remains the same.

Brahman created the three aspects of himself: The Many.

The creative aspect of Brahman who uses Prakriti to create the universe is known as Brahma.

Brahma uses the seven elements to create everything in the universe. These elements are 1) Pure Reason 2) Egoism 3) Ether 4) Air 5) Fire 6) Water and 7) Earth. These elements are used to create forms which are unable to show their Jivatma as they are so heavily coated in matter.

Brahma also created the Indriyasas such as the senses and organs which are actively able to show the power of Jivatma.

Additionally, Brahma created the Devas (deities) who carry out the laws of Ishvara and make sure that all living things receive their Karma while also helping those who serve them well. There are five ruling Devas each of which are associated with an element of creation: 1) Indra is associated with the Ether 2) Agni is associated with fire 3) Vayu is associated with air 4) Varuna is associated with water and 5) Kubera is associated with the earth. There are also Asuras who are the enemies of the Devas. Brahma also created Manah (the mind) along with minerals, plants, animals and men. This completed the creation of the worlds where the Jivatma was able to unfold and is presented in what we call evolution or Samsarah. Samsarah is visualised as an ever turning wheel.

The second form of Ishvara is the one that cares for and maintains the universe. He is known as Vishnu. Vishnu created form out of Brahma’s creations and in so doing, he breathed life into the forms and thus lives within all things as Prana. Prana is a piece of Vishnu which is in all of us and is what gives us consciousness.

Vishnu is also depicted in Hinduism in the form of Avataras which is when Vishnu presents as divine manifestations. The purpose of these manifestations is to bring out a particular result, usually used when things are going badly in the world and steps must be taken to correct the path of Samsarah.

The ten most important Avataras are

- Matsya – the fish

- Kurma – the tortoise

- Varaha – the boar

The first three Avataras are said to mark important steps in evolution.

- Narasimha – the man lion

- Vamana – the dwarf

- Parashurama – Rama of the Axe

- Rama – the perfect man (his story is told in the Ramayana)

- Krishna – the manifestation of Divine love and wisdom (his story is told in the Mahabaratam)

- Buddha – the teacher of truth

- Kalki – the Avatara that will end the Kali Yuga (in which we currently live) and begin the Satya Yuga – a new era

The development of humans is reflected in these later Avataras.

Lastly, the form of Ishavara whose role it is to dissolve that which is no longer needed is called Shiva or Mahadeva.

All three aspects of Ishvara are reflected in humans in some way.

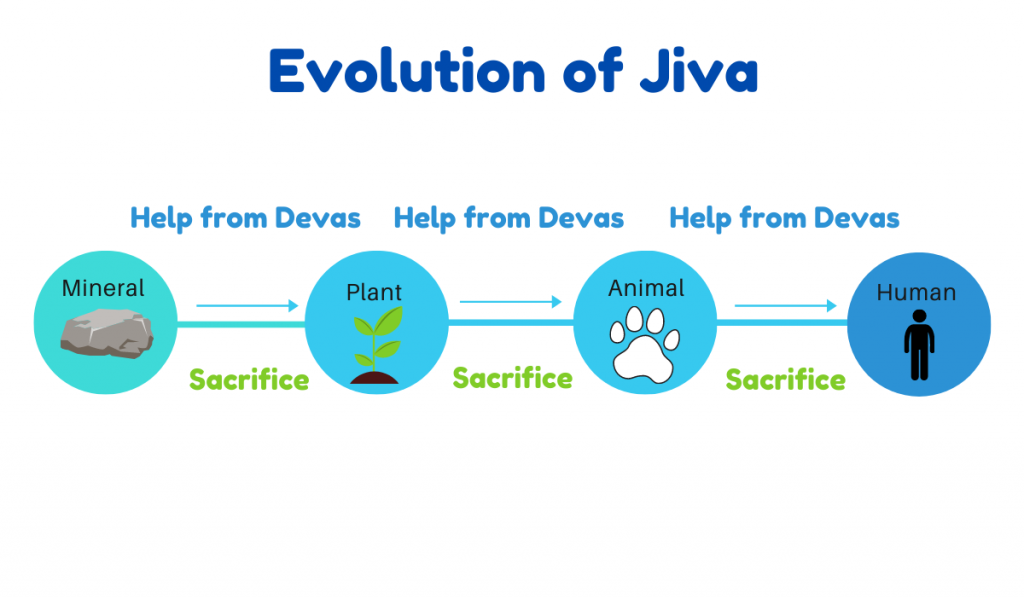

All of the forces we have seen thus far are embodied in the way that Jiva (the spirit) passes from body to body, each new body improving as the Jiva’s power develops. This is called re-birth, re-incarnation or transmigration. Jiva is the portion of Brahman found in each body, it is like the seed that Ishvara puts into matter. In the beginning of the universe, Jiva was the opposite of Ishvara, namely unwise and powerless but Jiva eventually grew into wisdom and power. This is the process of evolution, and each spirit that is placed on the earth goes through this evolution.

A young Jiva begins in the mineral world, tormented by earthquakes, volcanoes, landslides and water. These catastrophic events (which characterised the early days of our planet) act to awaken Jiva and thus prompt Jiva to realise he is not alone. Once they are awoken the Jivas could then develop into plants. Plants are more conscious of the world and as this consciousness grew, plants became more complex (e.g. trees) and eventually developed into animals. In animals, the Jivas developed much faster and gained mental power. Eventually their senses grew so much that they needed the human form, and this is where evolution has stopped.

The Jiva is what drives evolution and with the help of the Devas, Jiva is able to create new bodies.

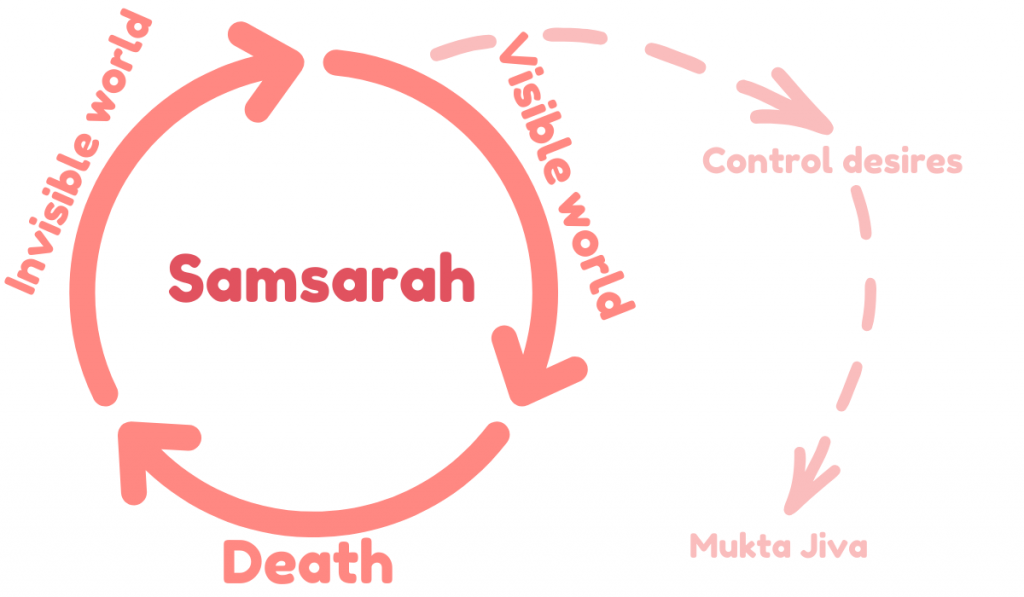

It must be noted that the evolution of the Jiva is not always a linear ascent and that there can be times of slower change, times of backward change and times of twists and turns. An example of this is when a Jiva which has reached the human stage may go back to the animal, plant stage or even further back until he better learns to use the human form and can therefore rejoin human society. A Jiva will be tied to this cycle of birth and death which will continue for as long as the Jiva desires things which belong to the earth. Only when he no longer desires anything will these ties be broken and he will be free; he is then a Mukta Jiva (a free spirit). Muktas can remain on earth to help earth’s progression as Rishis, Kings or people who live only to help others.

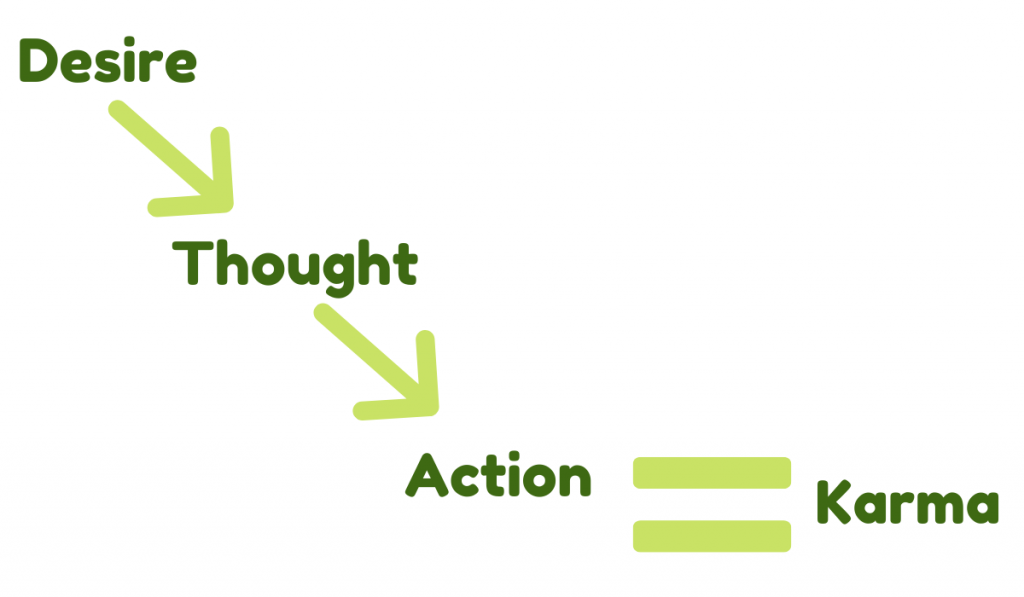

Perhaps the Hindu concept that we are all the most familiar with is Karma. In Sanskrit Karma means “action” though in Hinduism we use it to mean the connection between what has been done and will happen in the future. The essential teaching of Karma is that: Man sows the seed of what he wants to reap.

In simple terms, we desire something, we think about it and we act to gain it. This is the regular order of things whereby each action is preceded by thought and desire, and it is these three things that make up our Karma. Our desires determine our thoughts and attract objects. For example, if you desire love you will eventually gain the opportunity to be loved. Next, our thoughts determine our character meaning that the more we think about something the more we become the thing. If we think kindly then we become kind and conversely if we think cruelly we become cruel. Finally, our character determines our actions meaning that a kind person acts kindly and a cruel person acts cruelly. As we constantly change, our Jiva develops and we can change our desires, thoughts and actions. In order to change our karma we have to go to the root of our desire and stop ourselves from desiring something and we must only allow ourselves to desire that which brings happiness. It is said that the older the Jiva the wiser it is and therefore able to control its desires and only desire that which brings happiness.

Sacrifice is also an important religious principle in Hinduism though its meaning may not be exactly what you presume. Sacrifice of other things is supposed to teach a person that the ultimate sacrifice is of oneself. Even Ishvara sacrificed himself so that he could bring separate elements of himself into being. This is the primary sacrifice upon which the Law of Sacrifices or Law of Life is based. Sacrifice is about pouring out life for the benefit of others, and this occurs naturally in our world. Young Jivas are sacrificed forcibly and progress through different forms. For example minerals pass into plants which sacrifice the minerals to support themselves and gain nutrition, these plants are then sacrificed to animals which are then sacrificed to humans. Humans even sacrifice the bodies of other humans in acts of war and cannibalism. All of this sacrifice helps the Jiva progress as bodies are sacrificed for the benefit of others. Sacrifice in this sense, namely for the good of others, leads to increased return in the future. In simple terms this means sacrificing some of our goods now will bring us increased possessions in the future and if we sacrifice some enjoyment here on earth, we can enjoy much more in Svarga (heaven). Once the Jiva has recognised the universality of this law he can sacrifice himself deliberately in order to benefit others just as Ishvara did, thus showing that the nature of Ishvara is in the Jiva and lives within all matter.

Sacrifice shows us that all lives are interdependent and only by recognising this interdependence can we thrive. We are reminded that sacrifice should be a joyous thing as we try to see how little we can take and how much we can give to the world. Through sacrifice we can learn that we function to live for others and that we are simply channels for the will of Ishvara given that every sacrifice is for him and this is how we can achieve liberation.

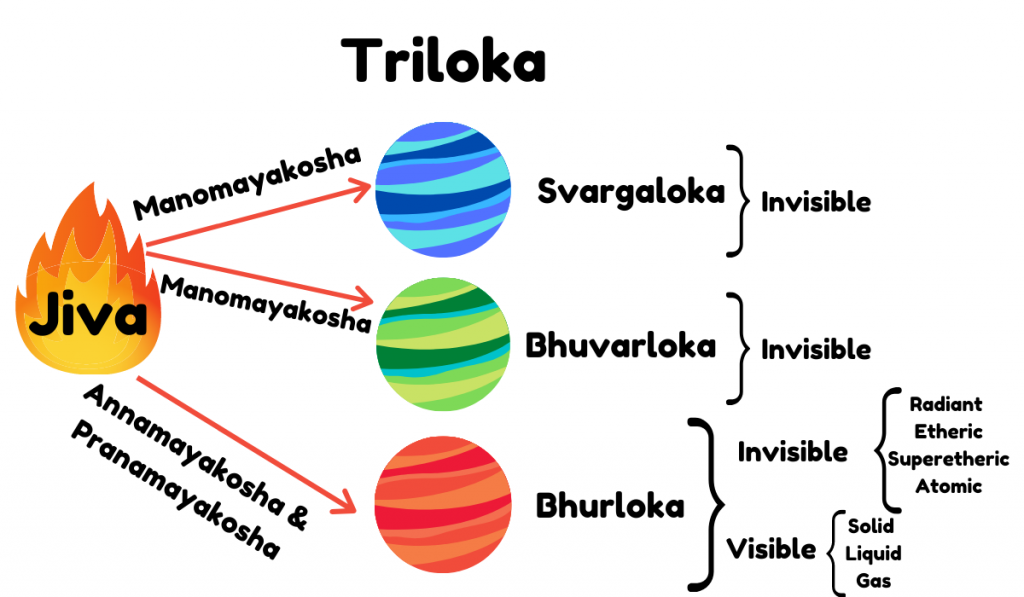

Liberation here can mean the progression of the Jiva through the worlds, both visible and invisible. Hinduism teaches that there are three worlds known collectively as Triloka. These worlds bind Jiva to the cycle of death and birth and were created at the beginning of the Day of Brahma (the creation of the universe) and will be destroyed at the end of the Day of Brahma (the end of the universe).

The three worlds are:

- Bhurloka: The Earth. This world is partly visible and partly invisible to us as we cannot see the smallest atoms that make up this world nor can we see the Jiva.

- Bhuvarloka: This is the world between earth and heaven and is invisible to us.

- Svargaloka: This is the heaven world and is invisible to us.

In each world there are things that make up the basis of all forms, on earth these are:

- Solid

- Liquid

- Gas

- Radiant

- Etheric

- Superetheric

- Atomic

The latter four are known as the ethers and cannot be seen by us (as previously mentioned).

While on Bhurloka the Jiva is composed of the Annamayakosha (made up of solids, liquids and gases) and the Pranamayakosha (made up of ethers which we cannot see). In Bhuvarloka the Jiva is made of Manomayakosha, the part of the mind ruled by passions, and in Svargaloka the Jiva is ruled by the part of the mind where emotions and thoughts reside.

Therefore a Jiva’s cycle is one of life in the visible world followed by death, followed by life in the invisible worlds, followed by re-birth. Eventually the Jiva grows tired of this cycle and no longer feels the need to seek pleasure for himself, he then only stays in the invisible Lokas, either using his earthly form to service Ishvara or leaves behind earthly forms and enters into Brahman.

Read the next instalments of this series here: